Starting in the 19th century, Milan definitively overtakes Venice, which since the second half of the 15th century had been the driving force of Gutenberg printing in Italy. From Venice, in 1810, had come Antonio Fortunato Stella, a diplomat of the Serenissima who after abandoning his career in politics became a true forerunner of the trade of publishing. He settled in Contrada Santa Margherita, the district of booksellers just behind Teatro alla Scala, where Vallardi (since 1750) and Ricordi (1808) had also set up shop. Stella called on illustrious collaborators, including the poet Giacomo Leopardi, invented series for a feminine audience (Biblioteca amena e istruttiva per le donne gentili, 1822) and pointed out the first cases of literary piracy.

The history of printing until the advent of today’s new media is also that of one of the sectors that had the most influence on the identity of the city of Milan. Among the most important publishers of the early days of this industry, the Fratelli Treves (1861), the brothers who educated entire generations of Italians from the unification of the nation until 1904, published the most highly acclaimed authors like Grazia Deledda, Luigi Pirandello, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Giovanni Verga, as well as Flaubert, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Charles Dickens, among the foreigners. Another writer for the Corriere di Milano of the Treves brothers was the Neapolitan Eugenio Torelli Violler, who went on to found Il Corriere della Sera (1876), now the daily newspaper with the widest readership in Italy, together with the much younger La Repubblica (1976). Other great publishers of the 1800s included Sonzogno (1818) and Ulrico Hoepli (1870). The latter, Milanese by adoption, oriented towards the spread of technical and scientific knowledge, was responsible for the construction of the Planetarium that bears his name, located inside the Giardini Indro Montanelli, which in turn are named for one of the most outstanding Italian journalists of the 20th century.

In the 20th century outstanding figures in publishing include Mondadori, a true leader in the sector today, whose continuous, diversified rise – from scholastic manuals to radio-television production – begins at the time of the founder Arnoldo, who began his career as an errand boy in a print shop in the province of Mantua. Others are Rizzoli (1909), founded by Angelo Rizzoli, who grew up in the orphanage of the Martinitt, when he had just turned twenty; Bompiani (1929), Corbaccio (1924), Bignami (1931), Feltrinelli (1954) and Ugo Mursia Editore (1954), the “publisher of the sea” who translated Conrad and donated to the city his collection of books, figureheads and nautical objects, now the “Museo-Biblioteca d’arte marinara,” conserved at the Leonardo da Vinci National Museum of Science and Technology.

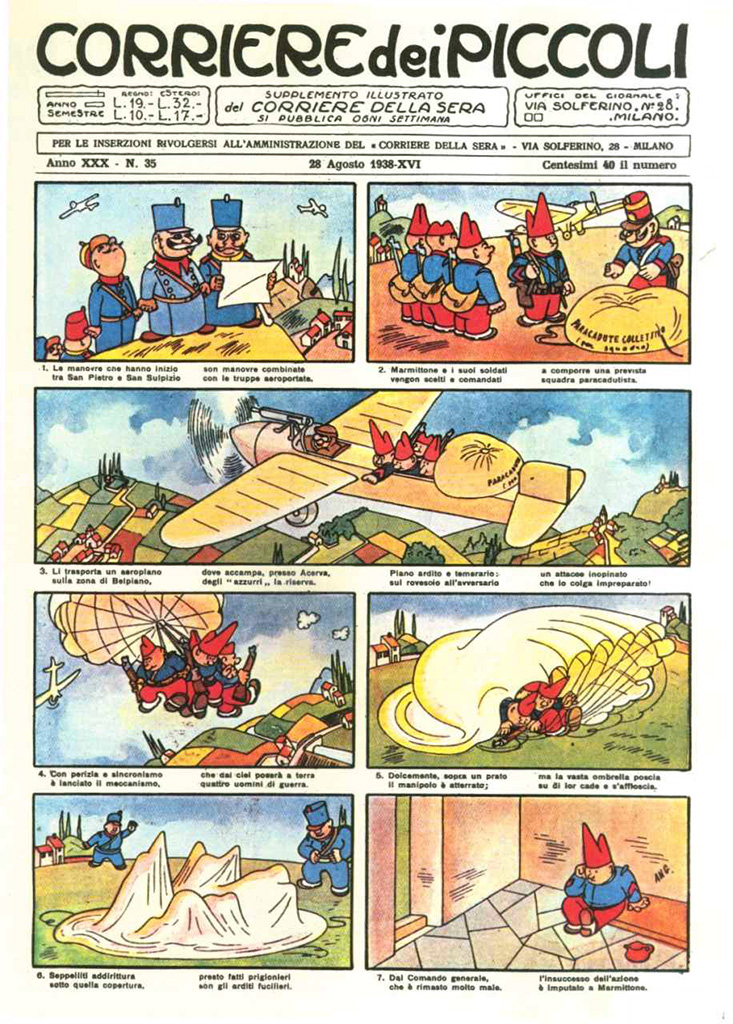

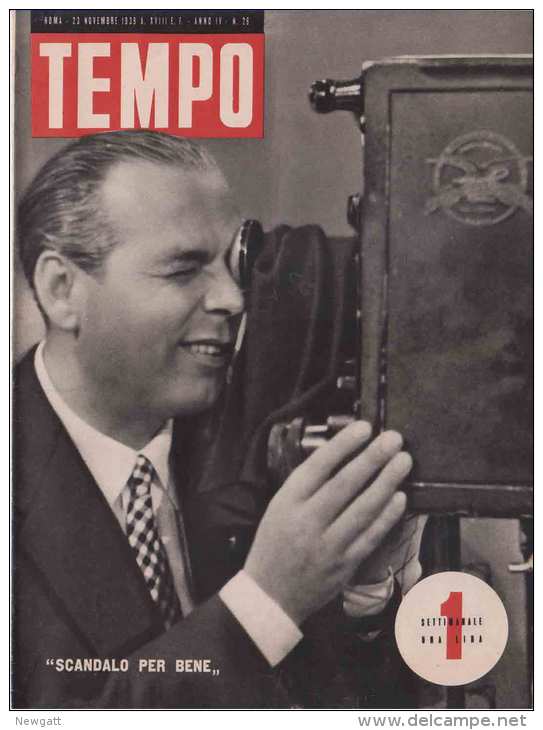

In the 1920s and 1930s, to the cry of “Libro e moschetto, fascista perfetto” (book and musket, the perfect Fascist), the Mussolini regime exploited the publishing industry, which also through the many illustrated magazines, mainly promoted by Mondadori and Rizzoli, was able to reach a mass audience. Milan saw the proliferation of editorial boards of some of the magazines destined to produce models of reference for today’s print periodicals. Among the most popular publications: Omnibus (1937-9), directed by Leo Longanesi, who founded his own publishing house in 1946; Tempo (1939-76), the first photo magazine, with graphics by the artist-designer Bruno Munari until 1945; Il Corriere dei Piccoli (1908-1995) and the women’s fashion and lifestyle periodicals that soon opened their columns to themes of feminine emancipation, from the forerunner Corriere delle Dame (1804-1875) all the way to Sovrana (1927), known since 1938 as Grazia, which is still on newsstands today.