Thanks to its geographical position and the specific forms of manufacturing expertise in its outlying zones, Milan became an open, vital laboratory of Italian civil society. A pioneer in terms of artisanal growth, trade and no less importantly social and even political transformations, the city took on the role of the economic, industrial and financial capital of Italy thanks to its distance from the Roman political establishment and to the industrious character of a dynamic middle class active across the territory.

From the first thermoelectric plant in the nation – the second in Europe – to its leadership of Italian fashion in the 1980s, Milan has profoundly influenced the history of national design, reaching its apex in the period after World War II. The complex roots of this success lie in the contamination with the arts and the ante litteram experimentation encouraged by enlightened entrepreneurs, professional schools, universities, academies and art galleries.

Alongside this creative approach to business, necessarily flexible and versatile in a fragmentary national context, the invention of new materials as surrogates for the raw materials of the 1930s and 1940s was another decisive factor for growth.

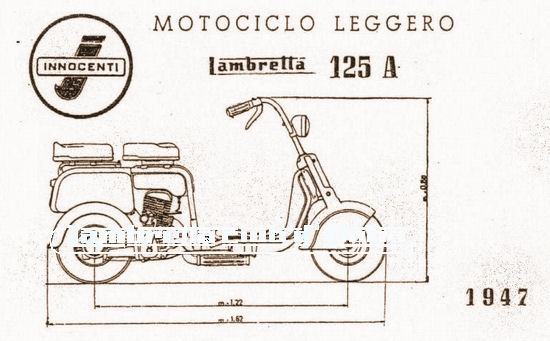

From the early 1900s, the Lombard capital excelled in the production of new means of transport and mechanical parts. This was the home of brands known all over the world: Breda (1886), Isotta Fraschini (1900), Alfa Romeo (1910), as well as Touring (1926) and Innocenti (1931), which produced the iconic Lambretta scooters (1947). The list could also be extended by including Bugatti (Ettore Bugatti was Milanese) and even Ferrari, because it was precisely from Milan that Enzo Ferrari took his first steps in the industry.

The evolution of design was nurtured by specialized publications and prestigious exhibition facilities. First of all, the Triennale di Milano which hosted, in 1947, the exhibition “RIMA, Riunione Italiana Mostre Arredamento,” underlining the fact that it was precisely in Milan that design was spreading as an accessible code of modernity, an expression of lifestyle and taste.

The magazines represent fundamental factors in the research and the often lively, militant debate about architecture and design. Directed in alternating phases by outstanding designers and critics, the Milanese magazines reached heights of international renown and, above all, contributed – in the utterly Italian problematic approach to theory – to the contamination among disciplines, intersecting with new languages and professional figures. Magazines founded in Milan include: Domus (1928), La Casa Bella (1928, Casabella since ’33), Edilizia Moderna (1929), Interni (1954), Casa Novità which then became Abitare (1961), Zodiac (1957), Caleidoscopio (1964), Ottagono (1966), as well as Stile Industria (1955-63), Artecasa (1958-60), Modo (1977) and Spazio e Società (1978).

In the 1950s of the economic boom, legendary objects took form as a result of the brilliant cooperation between design and small and medium businesses: Sottsass and BBPR for Olivetti; Ponti for Cassina and Venini; Nizzoli for Necchi; Albini for Bonacina & C.; Munari and Mari for Danese…

To honor the growing autonomy of Italian design, in 1954 the La Rinascente department store organized the Compasso d’Oro award, taken over in 1964 by ADI, the Association for Industrial Design. In the 1960s, parallel to the emerging critique of the society of consumption and a more conscious distance from the historical avant-gardes, the inspired formal research of many designers working with companies continued, capable of combining culture, production and communication. Castiglioni for Zanotta, Flos and Gavina; Zanuso and Sapper for Brionvega; Bellini for Olivetti, La Rinascente, Irradio and Cassina; Magistretti and Mangiarotti for Artemide, Colombo for O-Luce, Aulenti for Kartell… In the exhibition curated by Emilio Ambasz Italy: The New Domestic Landscape (MoMA, 1972), which brought Italian designers great acclaim abroad, old and new generations of designers converged, capable of going beyond the crisis to enter a modernity that had become more complex in terms of the range of users, the habits and languages of a postindustrial and post-ideological scenario. In the early 1980s the experience of the Memphis group, founded in the apartment of Ettore Sottsass on Via San Galdino, represents the last episode, of greatest experimental freedom, of Milanese 20th-century design.