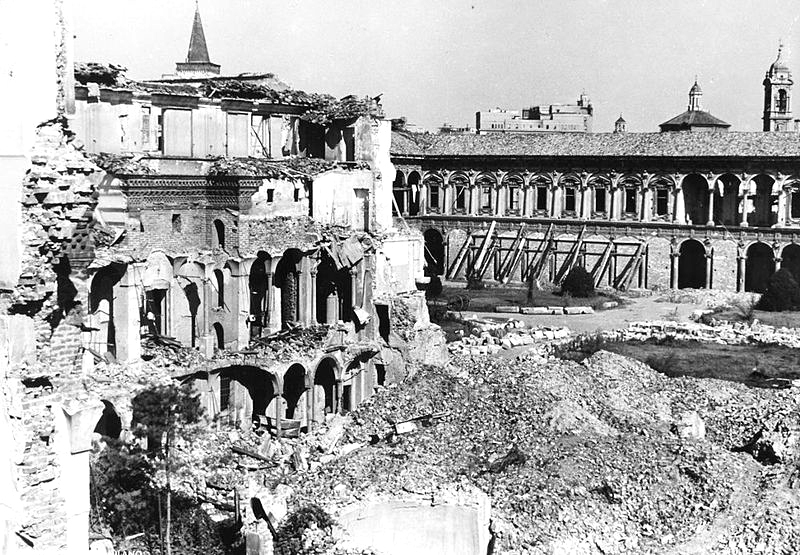

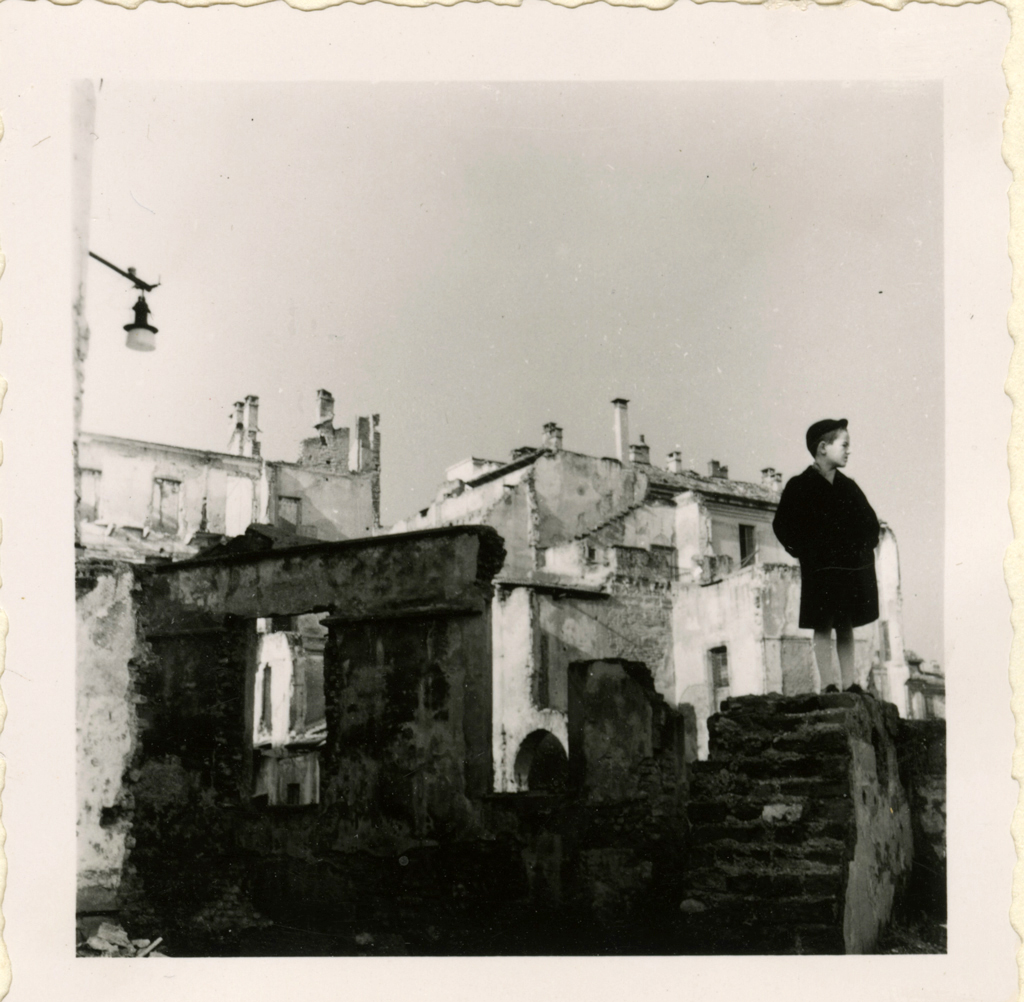

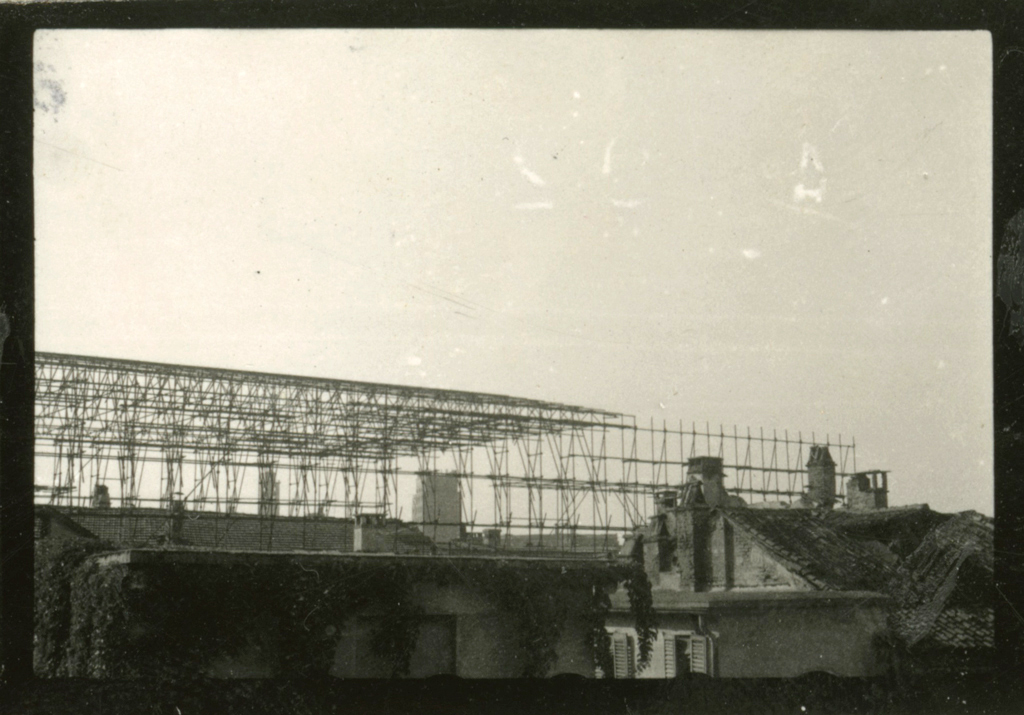

During World War II Milan suffered serious damage to the urban fabric and its monumental heritage. A strategic target of the Anglo-American alliance due to its industrial and commercial role, together with Turin and Genoa, the city was repeatedly bombed in air raids from 1940 to 1944. While the first strikes caused limited damage, the bombings of October 1942, the more tragic ones in August 1943, and those of 1944 profoundly and permanently altered the image of the city.

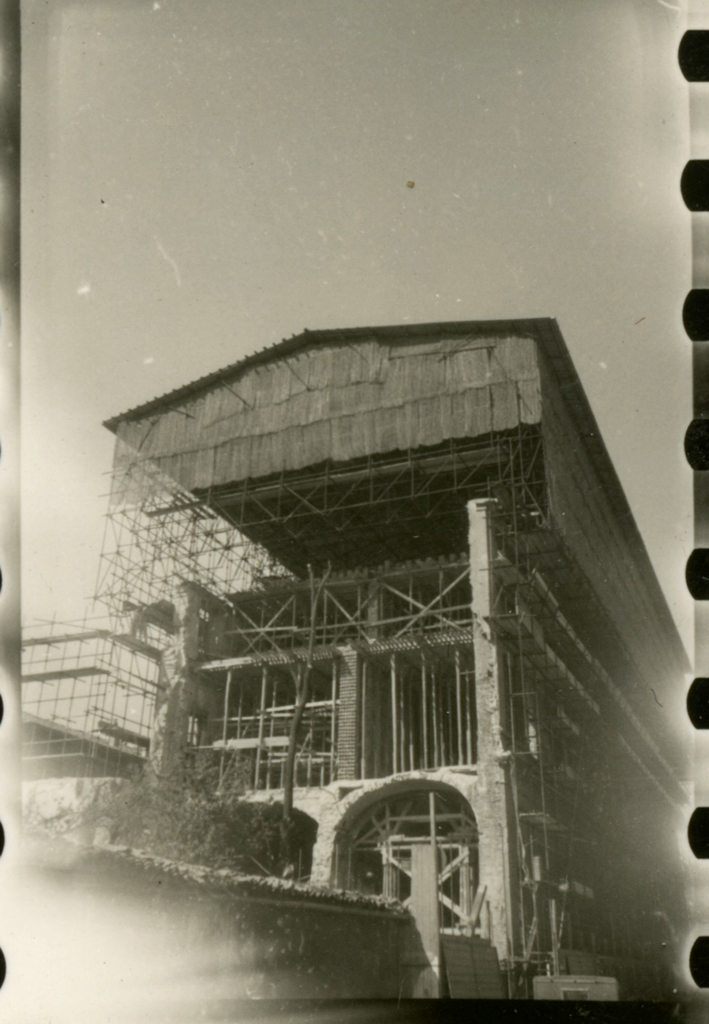

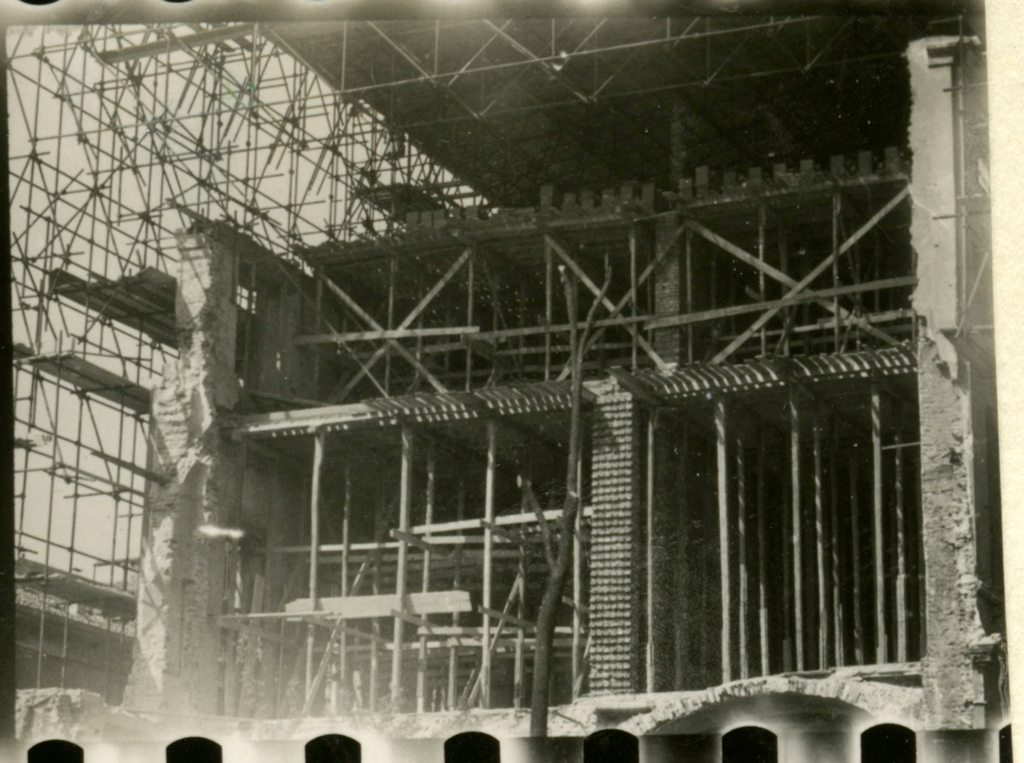

The sixty air raids focusing on the Lombard capital caused tens of thousands of deaths and were often the cause of the urban-architectural transformation of the city in the decades after the war. One third of the edification of Milan was destroyed by the bombings and the fires that broke out, or by demolition, necessary or rash, which took place for the reconstruction. Over 65% of the buildings protected by the heritage authorities were damaged in spite of national defense measures and the safeguarding orders that Milan itself, with great foresight and technical insight, had dictated to the National Education Ministry, in charge of cultural activities and assets at the time, under the Fascist government. Kilos of sand, reinforcements and struts saved the Last Supper of Leonardo da Vinci and the Ciborium of St. Ambrose, but many public and private works of architecture vanished forever, at least in their original version: the Dal Verme, Verdi and Filodrammatici theaters, Casa Velasco and Palazzo Melzi di Cusano at Porta Romana, the stables of Villa Reale, Palazzo Ponti facing Brera, or the Arcimboldi, Cicogna (Via Unione) and Cramer (Via Fatebenefratelli) buildings, just to name a few.

The loan of one billion of the lire of the time obtained by the municipal government in 1944 just barely sufficed to clear the rubble from the city. Montestella, the artificial hill in the new experimental QT8 district designed by Piero Bottoni (1947), was made precisely thanks to the use of war debris, an eternal reminder of the lost city. The effects of the war and at the same time of real estate speculation spurred on by the demands of a population that had more than doubled already in the decade prior to the war, erased the intersection of popular streets and wealthy neighborhoods, and entire areas were modified in terms of their layout. For example, this was the fate of the disreputable Bottonuto, the “red” neighborhood behind Piazza Diaz, and of many other zones, at least until the Master Plan of 1953.

On 11 May 1946 Teatro alla Scala made its triumphant return, while the gaps in the wounded city fed the debate on reconstruction to match the image of the past, or works done with greater design freedom. The most positive results of this dialectic led to the construction of buildings that are symbols of modernity: Torre Velasca (BBPR, 1956-8), the Pirelli skyscraper (Gio Ponti, 1956-61) and the Padiglione d’arte Contemporanea (Ignazio Gardella, 1951-4) are some of the works of architecture that contribute to enhance the new visage of Contemporary Milan.