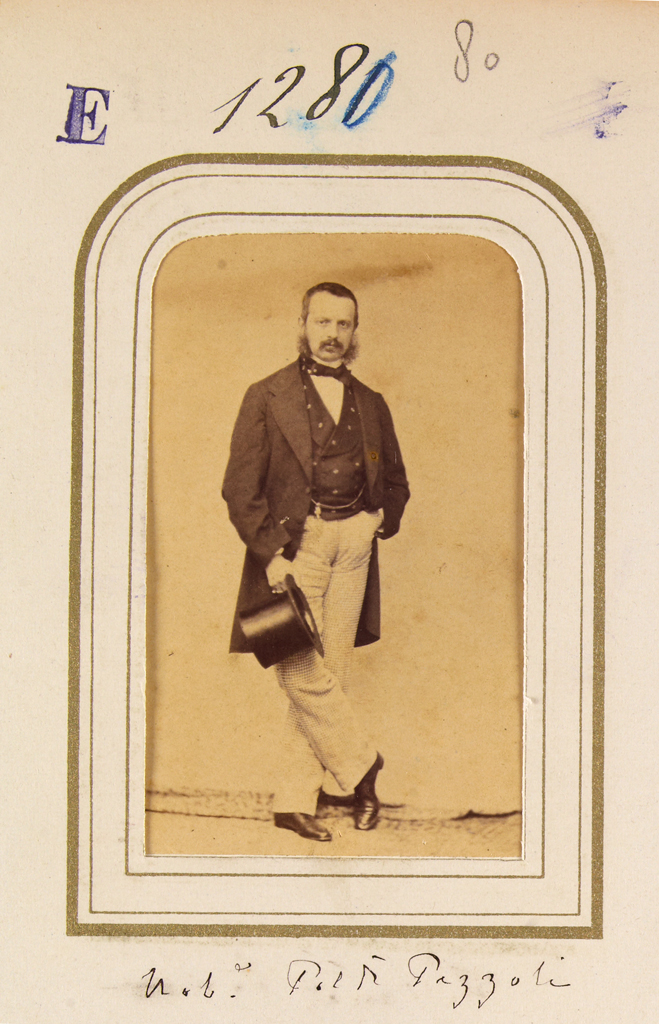

We can imagine the rage amongst the Austrian elite. What the devil does that Poldi Pezzoli have in mind? Why are museum directors from all over Europe flocking to pay him homage? You offered no reply. Instead, you talked things over with cabinetmakers, blacksmiths, ceramists, painters, upholsterers. Your collection, with its precise aims, grew day by day. Works from the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Baroque. Names that were already milestones of Italian art: Piero, Perugino, Botticelli, Pollaiolo, Mantegna, Tiepolo… not simply masterpieces, not simply the collection of an aristocratic. You were an intellectual, not a wealthy eccentric.

The new nation, the one beating in your heart, had to know about its artistic glories, and to stimulate young talents. In art, but also in science and crafts. That is what your home was becoming: the laboratory of taste of a nation. You loved Dante – as did Mazzini and all the patriots of the Risorgimento – as the father of the language, of course, a great poet, certainly, but also as an exile, in search of a homeland, the same one you were searching for. In 1851, for the first Universal Exposition, that of the Crystal Palace of Paxton, keystone of modernity, the young Giuseppe Bertini made monumental window, a feat of Lombard technical prowess, entitled “The Triumph of Dante” (it was a great success, winning first prize). Art, crafts and patriotic ideology, bonded together. You were there and you wanted it for your little cabinet, your study, and Bertini made you a replica. Then you had a bronze grate made, to divide the studio from the rest of the house, imitating the medieval bronzes of the Trivulzio candelabrum, in the cathedral for centuries. You had the walls adorned by plasterers, painters and decorators, creating something that was no longer an imitation of the Lombard Middle Ages, but practically a work of Art Deco, before its time.

Your project was clear. Literature, opera, technology, the intelligence of the hands of craftsmen and artists, represented the human capital on which to base political opposition and the identity of the nascent Italy. Your house had to become a pedagogical museum, a compendium of reference for the people of Milan. A place in which to admire beauty, to study techniques, to learn in order to reproduce, spread and invent. You knew this, without regrets. At the age of 39 you had already made your will. “I hereby order that the apartment in which I live, in the wing between the garden and the two courtyards of my palace at Via del Giardino 12, with the Armory, the paintings, the art works, the library and the furnishings of artistic value located there at the time of my death, be made into an Artistic Foundation for public use and benefit in perpetuity under the same regulations applied for the Brera Art Gallery.” This was written. And from that time on, any artist and artisan of Milan could enter, free of charge, to admire and study. To perpetuate our national identity through creative genius.

Many years later the cruelty of World War II devastated the decorated rooms in your palace. A firebomb destroyed the painstaking efforts of antique and modern talents. But the collection, your collection and ours, was saved. Together with your little study, which remained intact, which we can still admire, moved. The cabinet where you wrote your will, where you died of a heart attack, a cruel fate, two years before the museum, your most beloved creation, was opened to the world.