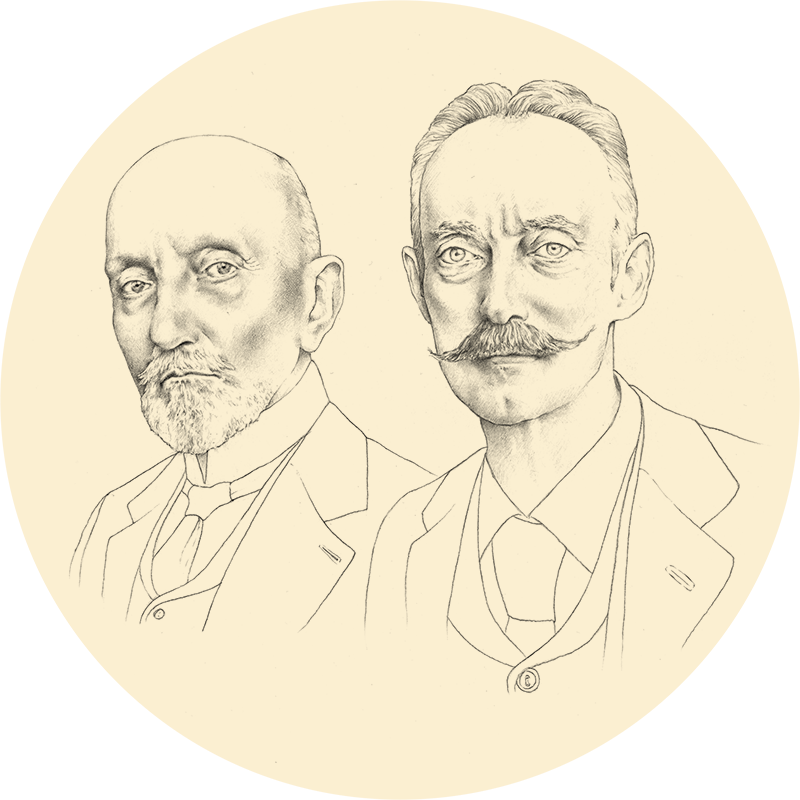

Though similar in your passion for art, your ways of behaving were very different. Fausto, you were an outgoing bon vivant, the opposite of the more reserved, quiet Giuseppe. Gossips said the young Carolina Borromeo d’Adda had been introduced first to you, since after all you were the elder brother, and therefore should have been the first to settle down. But you didn’t like her, so you made haste to introduce her to your brother, leading to their marriage. You weren’t interested in continuing the lineage; you could leave that task up to your brother.

Your wedding, Giuseppe, was impeccable, with fine announcement cards including a commemorative medal from the Johnson foundry. A Borromeo d’Adda was entering your home, the result of two families dating back to the Middle Ages of the nation. She loved you from the outset, and you really made a very fine choice. She followed your reconstruction by analogy of your past with great interest, she who had nothing to prove by ancestry, who had grown up in a luxurious building on Corso di Porta Nuova, the most elegant street of the 1800s (today we all call it Via Manzoni), a place so beautiful and so well made that it seduced the young Stendhal, who fell in love with Milan and its architecture. The palace you two reconstructed seemed to be keyed precisely to that sumptuous street. A first courtyard, a second one, and then – on Via del Gesù – a bend into the facing building, also yours, as a third courtyard open to passersby, faced by yet another of your philological projects: a palazzetto of the early Lombard Renaissance, in terracotta. Conceived for the progeny, for the descendants of the family.

Carolina was a prolific and devoted mother. And she had fun. Of course she had fun, because she had realized that the man she had married, apparently serious and impeccable, possessed a vein of folly, of playful irony he couldn’t really disguise. Which he had passed on, perhaps, to his children and grandchildren. Years later, one century on, Pasino, an engineer in his seventies by then, at the start of the 1970s, amused himself at the villa in Cardano by dressing up as a flower child, a hippie, with the same attention to detail as his ancestors who delighted in creating tableaux vivants, photomontages based on antique Renaissance altarpieces, with members of the Bagatti Valsecchi and Greppi families posing for posterity.

It was a game. A very serious game. Even your endless calling card, Giuseppe, with its list of titles, was serious. Yet also ironic. Not that they were falsehoods: you were really a member, the president or director of all those boards. You were really two brothers devoted to beauty and philanthropy. You really reconstructed or restored the villas and estates of much of the Milan aristocracy, and all those distinctions were more than well deserved. But put down like that, one after the other, seemed like yet another tale of a project of Bagattization of the past. Your life itself, perhaps, was your real work of art. Not false, not true. Plausible. Like when you were kids, and you said to each other: let’s play that I am a baron and you are a stableman. And vice versa.

The coffered ceilings, the friezes, even the dishes, the tableware, all designed and all decorated with coats of arms, insignia and ornaments invented by you for your family. A philological labor that required the help and concrete contribution of the finest craftsmen available. Because things, prior to being antique, or beautiful, had to be made well. With painstaking patience, with the precision of the miniaturist. Of all the emblems, perhaps too many for your young stock, the one that is the most authentically yours, the most ironic and the most moving, though, is a simple shield in yellow and red, bearing not a lion rampant, not a griffon or an imperial eagle. No. It bears a simple boot. A shoe. Bagatti was the name of your father, before he became a Valsecchi, before he became a baron. Like “bagatt,” shoemaker, in Milan’s dialect. Titles and honors are all well and good. But you are, you seem to be telling us, first of all cobblers, sons of artisans, who have ennobled with their art not only their home, but the entire city as well.