Those were the years when, in the world – London, New York, Paris – wealthy magnates or young philanthropists wanted to live in mansion of impeccable taste. You knew them, they knew you. But there was one important difference. Franz von Lenbach, in Munich, had an Italian-style neo-Renaissance villa built, while Isabella Stewart Gardner erected a Venetian palace of sorts, in Boston. You didn’t have to dream about living in an Italian city; you were already in Milan, with your house at your disposal.

And it was to be a house, not a museum. A house in which to live, to meet people, to raise a family. After your mother’s death, you devoted all your time to the search for paintings, ornaments, furnishings. In Milan, in Lombardy, in the valleys, the farmhouses. You designed everything. Everything had to be part of the overall project. What was lacking could be inserted. You knew that History is, above all, a narrative. Your lineage deserved a story. A past made into art, and artfully made. A private Renaissance that even extended into your properties outside the city, like the estate at Belvignate, studded with royal lilies (a clear tribute and support of the House of Savoy, and the symbol of the Florentine Renaissance).

You were not interested in knowing if the results would seem true or false. You were not seeking truth but, like authentic storytellers, the plausible. You wanted technical exactitude, the precision of the craftsman. From a Renaissance painting to a modern frieze, what counted was that it be perfectly made. As your father would have done. You searched for the finest artisans, and at the same time you rescued from oblivion works that would have been destroyed by the blows of modernity. As you did at Varedo, where in your country villa you reassembled several spans of the Milanese Lazzaretto, which was being demolished at the time to make room for new real estate speculation.

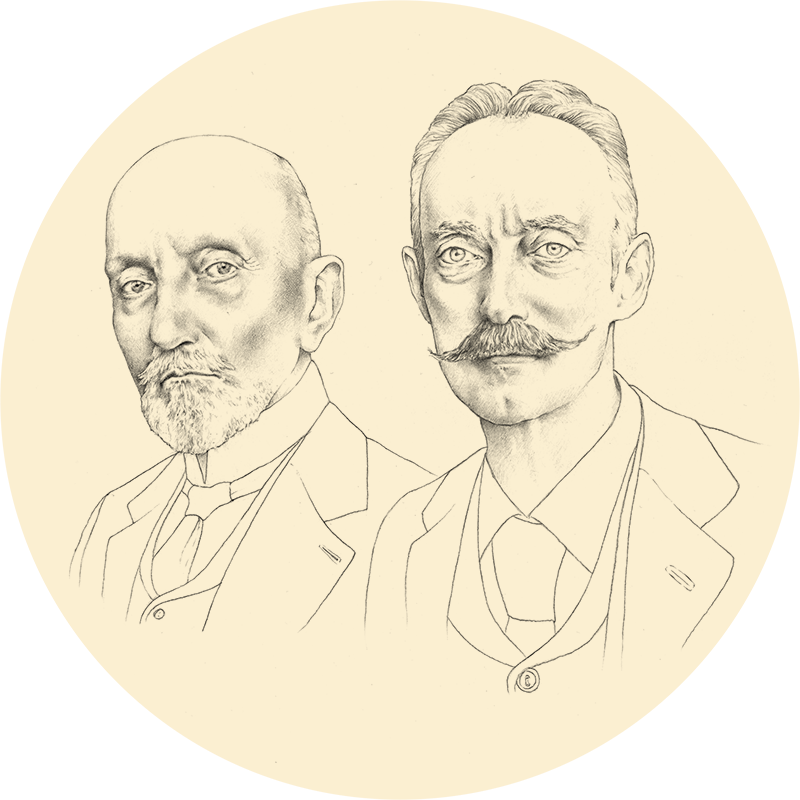

We should be clear about the fact that you were not scared of modernity, though. If it was time to buy a hat, Giuseppe, you went to Emilio Ghezzi in the Galleria, the brand new parlor of the Milanese, and you, Fausto, enjoyed yourself at the Arena, making flights with lighter-than-air vehicles. You were both consummate cyclists and founders, in 1870, of Milan’s “Veloce Club.” Your house was equipped with all the new comforts, including heating and running water. Only they were hidden inside wood paneling, under marble or wrought iron.

Some said you were guided by the hand of Luca Beltrami. The architect who was fighting to prevent the demolition of Castello Sforzesco in those days (yes, Milan even considered inflicting this wound, too, on the heart of the city). But it wasn’t true. While you respected Beltrami, the passion was yours, and it was authentic. Milan began to call on you for consulting and other activities. And you never failed to deliver: you redesigned the Porta dei Carmini at the Castle, you built the Villino Agrati (still visible today, between Via Mascheroni and Via Pagano), and you made a concert hall out of the abandoned Solarian church of Santa Maria della Pace. It was a patient work of restoration, with the hall devoted to the work of Don Lorenzo Perosi; here the presbyter performed many of his compositions, and here Arturo Toscanini conducted the premiere of his Mosé.