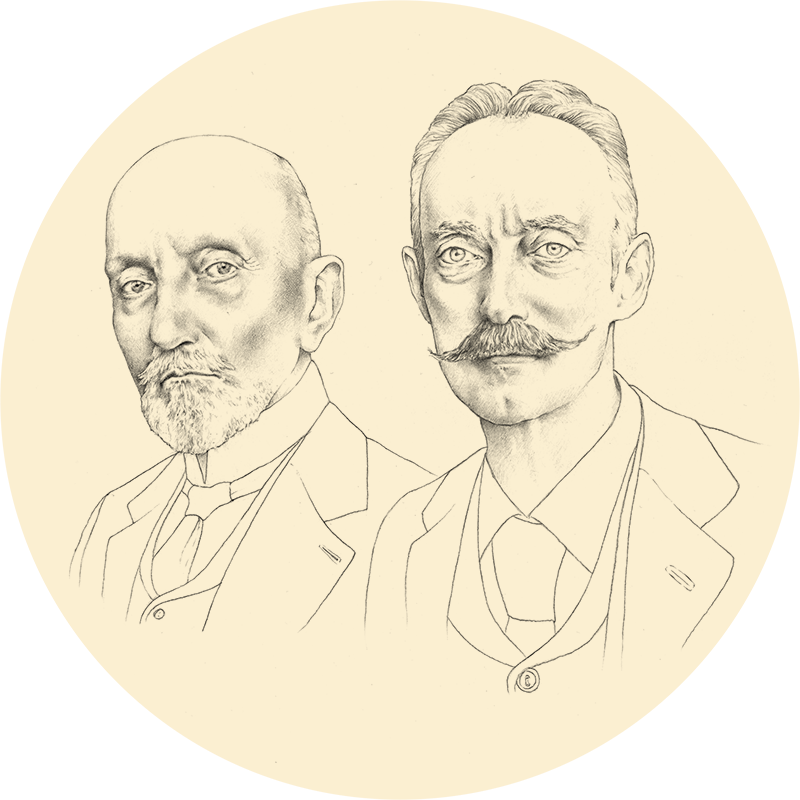

How much fun did you two have? You were just a couple of years apart, Fausto and Giuseppe. You grew up together, comrades, cohorts. Building your games from the outset, gravely, as only children can do. Because play is a serious matter. You shared everything, the ideas of one were those of the other. You both studied law, but neither one practiced it. You had a much more complicated game in mind, to play together. That of bringing the past back to life, of putting the lifeblood back into History.

These escapades, this dropping of a law career in the name of beauty, come from your father. He had studied science, with a degree in Mathematics from Pavia, but then he applied his precision as a man of science to art. He was an exceptional miniaturist, capable of working with ivory, enamel, metal, like few other Italians in those years. His name was Pietro Bagatti. He gained the second surname as an adult, when Lattanzio Valsecchi, his mother’s second husband who had just become a baron, decided to adopt him.

Pietro was good, really good. Watching him work, for you kids, was like seeing magic, enchantment. The sight of his works, like the enormous window of Saint Thecla and the Lions made by Pietro for the facade of the cathedral, was a source of filial pride. He was so good that by decree, in 1842, he made a nobleman of the Austrian Empire for his artistic merits. He could pass on the title of baron to his progeny not because he had been a fierce commander, but because he was an outstanding artist. You two never forgot that, as you were fantasized about your grandest, most imaginative game.

Your house was in a neighborhood still populated by lacemakers and dressmakers, with chickens in the courtyards, between Via del Gesù and Via Santo Spirito. Your mother Carolina, after her husband passed away, had decorated it in a dignified way, with that neo-late-Baroque taste that was so in vogue back then. A taste that didn’t match yours, though. You were not interested in fashion. There was an idea you had been nurturing for some time, all it needed was application. To transform passion into something concrete. To play, still, to have fun. But gravely, as in childhood.

If yours was a new nobility attained through art, you had to have a house that would be consistent with that legacy. An aristocratic dwelling where every detail, every room, every nook and cranny would be free of contradictions. An enormous formal workshop. A Renaissance mansion, the loftiest of Italian styles now that the nation was born, as young as your titles, yet ancient in its history.