That was your surreal, Dada side. Like a kid that had never grown up, never been tainted by the fatal grimness of the adult world. When you were twenty you enjoyed playing on the big terrace at your house with a small circle of friends, doing “bicycle races.” The game had been invented by Guido Crepax, when he was barely a teenager. You drew images of the most famous bicycle racers of the day, on cardboard, mounted on pedestals. Then you moved the pieces, rolling dice. For hours and hours. You continued with these games over the years, at your house or his house on Via De Amicis, also building little cardboard rings on which to move boxers. At the house in Val Sesia, with Mino Ceretti, your children and those of Alik Cavaliere, you invented and shot epic little Super 8 films. The director was Gianfranco Pardi.

You were not interested in power, in the conventicles of artists. “I stick with the monks and hoe the garden,” you once told Flavio Caroli. You were a humanist in the classic sense of the term, your life was made of things to do, things to imagine, friendships to nurture, not petty ambitions. After all, you were well aware of the fact that existence is this mixture of the tragic and the comic, a dreamscape we cross like puppets, marionettes brought to life only by a smile.

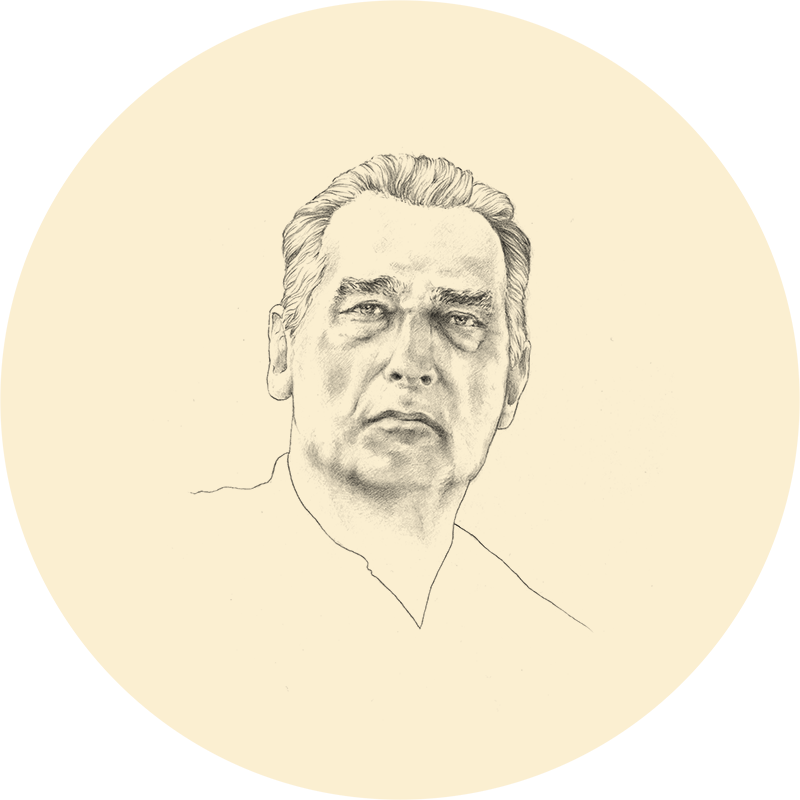

It required the right physique to have all these lives, Emilio. You had it. Even that particular careless way of dressing was your ironic way of toning down your natural elegance. You had a sculpted face, a toned body. Maybe this was another reason why the illness that afflicted you seemed even more malignant, even crueler in your case. You were weakened and tired, but you continued to work for your Milan. In the hospital, a few months before the end, you were still a member of the Monuments Commission of city hall, and you had found time to examine the project for a sculpture by Fausto Melotti to be placed at Piazzale Lodi.

Your friends – and you really had many, which is your true masterpiece: creating friendship – came to see you, at home, in the hospital, and though you were debilitated and tired you were the one to reassure them. You didn’t want to see sad faces, tears, it wasn’t necessary. “I’ve done everything,” you told them, “I’ve had everything. In the end, I can call it a day.” You had managed to get free of all the constructs people make about existence, you told your visitors. In this way, the “definitive secession” didn’t seem so dramatic after all. “When you’ve done what you wanted to do, in life, then in the end…”

How man “Emilios” were there, Emilio? They all went with you, when you left. Some people still look for them, on the streets of Lambrate. And on certain nights, when there is a full moon, it is still possible to glimpse them, dancing on the rooftops.